History of the "Old Lock" in Greenville, NC

- borrellij

- Nov 23, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 24, 2023

Our recent article on the antebellum river navigation lock in Greenville has been published in the North Carolina Historical Review.

This post is a general overview of a paper that we recently published in the North Carolina Historical Review. The article situates the construction of the Greenville Navigation Lock within the broader context of the internal improvements movement in North Carolina during the early half of the 19th century.

Prior to the advent of any major transportation network, North Carolina’s east-west waterways represented the only viable means of access to the inland areas of the state. A primary concern for North Carolinians was that these arteries of commerce were continually plagued with navigational hazards including shoals, irregular channels, snags, overhanging trees, submerged logs and seasonal variability ranging from prolonged periods of extreme low water to swollen “freshets” of high water. In the early 19th century, the state witnessed a substantial internal improvements movement among politicians and the local populace. Alongside the societal evolution that occurred with industrialization, the state government and publicly-oriented individuals began to invest in factories, railroads, steamboats, rivers, and plank roads in the hopes of fostering economic prosperity within the state. Championed by progressive government leaders and businessmen, the internal improvements endeavor in North Carolina sought to fix the natural roadblocks of commerce within the state.

The term “internal improvements,” much like modern society's treatment of terms like "climate change," became a politicized term to denote public works projects to improve transportation networks throughout the United States. Much of North Carolina's populace was split into two camps: those in favor of state-supported infrastructure projects, and those in favor of private individuals funding the works. Both sides recognized the need for improvements, but the contention was how to fund the effort. Many internal improvement projects on the state’s inland waterways were therefore only supported or financed as state-level political interest aligned with local need. On the Tar River, this effort culminated in an ultimately failed effort to construct a series of locks and dams that would make the troublesome river navigable year-round.

During the 1848-49 session of the General Assembly, an act was passed incorporating the North Carolina Railroad Company that included an amendment appropriating $25,000 for improving navigation on the Tar River. Local newspapers initially were in favor of this as a new steamship line had recently been established on the river, which brought with it the prospects of increased commerce. When the project on the Tar River began, however, Colonel William Beverhout Thompson, who had planned the work, appointed his assistant engineer to enact his vision. Over the course of the next three years, the baton was passed to three other engineers until H.M. Patton eventually completed the lock chamber in 1856.

"My own opinion is, that the work was commenced without a proper understanding of what was really required; and prosecuted with no fixed determination ever to finish it." - H.M. Patton, Engineer of Tar River Improvement (1856)

An additional $15,000 had been appropriated using state funds for the navigation locks, but the continual delays caused by natural factors, equipment failure, labor shortages, and the lack of a consistent plan among the civil engineers exhausted the entire appropriation by the time Patton completed the FIRST of a planned FOUR locks on the river. He didn't even have enough money left to build the corresponding dam that would make the lock functional! The state legislature quickly moved to strike the remainder of the second appropriation to try and recoup their losses. Within a month of the lock's construction, its foundation, which Patton noted had not been excavated to a proper depth, had settled and the lock gates were no longer operational. Local support of the project waned as the years dragged on, and in May 1857, George Howard from the Tarboro-based Southerner newspaper wrote that improvements on the Tar River were suspended and all the materials sold, “thus has $40,000 been squandered in another vain effort to improve our river."

The lock faded into obscurity, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reportedly removed much of the upper works to the lock in the 1890s as it had then become an obstruction to navigation. The "Old Lock" was still used by some locals as a fishing spot and landmark for travelers on the river during times of low water.

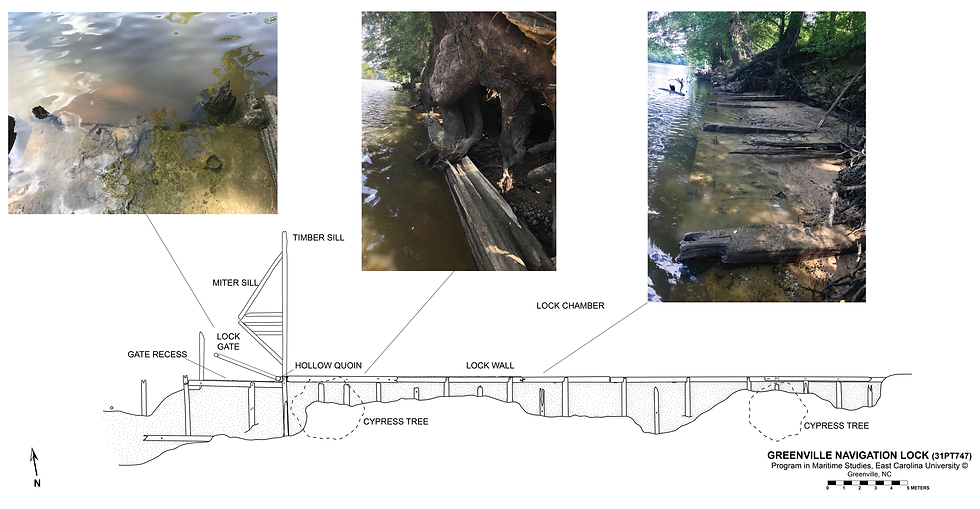

Interest in the archaeological remains of the Greenville Navigation Lock resurfaced when the Tar River became a center for recreation in the town. With the establishment of a Greenway Trail along the river containing various parks and access points for residents to enjoy the water, the City of Greenville designated the remaining lock structure as a local historical landmark in 2018. In 2019, we went out to the lock and examined the structure. We drafted a preliminary site plan for the archaeological remains, which consist of timber cribbing along the shoreline that represents the remaining lock wall. The lower portion of the upper lock bay, which incudes the lock gate, miter sill, and gate recess, were also present in this upriver section of the structure. It is likely that more of the lock chamber extends The site is registered with the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology as the Greenville Navigation Lock (Site No. 31PT747).

Future plans with this site include obtaining sonar imagery, and investigating the shoreline adjacent to the structure using varied remote sensing techniques. It has also got me curious about the history of civil engineering during the broader internal improvements movement in the 19th century. Were there other locks built in the state? If so, did they suffer from the same setbacks? Was there a common body of knowledge for the construction of navigational infrastructure among civil engineers of this time that might explain why no set of building plans were drafted for the Greenville Lock?

Preliminary research into all these questions and more suggests that yes, there are more locks to explore in North Carolina! Maritime infrastructure like the Greenville Lock remain an understudied topic in underwater archaeology. More and more we keep finding the remains of sea walls, timber crib structures, wharves, etc. that have broader implications for how people bridged the land/sea divide. This has become a main research interest of mine and I am keen to continue looking into these sites in North Carolina. Queue Whitesnake... "Here I go again on my own..."

Comments